Cindy holds a young horned lizard with a sweat bee - 3 September 2021 1:05pm

Dawn at the South Fork Cottonwood Headwaters section of the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve – 8 August 2023 6:27am

Four does on the west bank of the South Fork Cottonwood River east of Matfield Green – 24 April 2023 5:53am

The Milky Way with Andromeda Galaxy and Mars in constellation Gemini seen from open range west of Matfield Green west of Matfield Green – 13 December 2022 9:16pm

Desiccated broom weed in a brook in the North Branch Verdigris River watershed - 16 April 2020 9:15am

A heron rousing after bathing in Thurman Creek on the Rowe farm southeast of Matfield Green – 28 March 2023 8:44pm

A cumulonimbus storm cloud over open range west of Matfield Green – 17 July 2023 11:27am

Dry grass during early spring near Crocker Creek on the T. W. Burton Ranch - 2 April 2022 5:42pm

A flock of Migrating geese west of Matfield Green - 12 December 2021 5:50pm

Range west of the McBride compound - 31 October 2020 11:29am

A flushed quail in the center section of the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve (1) – 3 November 2020 2:55pm

Redbud trees in full blossom along the South Fork Cottonwood River south of Matfield Green - 24 April 2021 10:32am

Minnows feeding in Crocker Creek northwest of Matfield Green - 30 January 2022 5:32pm

A snag in Wildcat Creek on the Wight Ranch - 24 May 2021 2:04pm

Snagged driftwood in the South Fork Cottonwood River at Matfield Green - 5 June 2021 7:42pm

A pasture east of Matfield Green along 50 Road - 31 March 2020 1:19pm

Migrating geese in the Cottonwood River at Cottonwood Falls - 23 January 2022 6:18pm

Minnow and fawn along the South Fork Cottonwood River east of Cottonwood Falls - 11 July 2020 9:01am & 8:13am

Looking west from G Road south of Clements - 17 September 2021 5:06pm

An approaching storm front seen from the bluff over Sharps Creek Road east of Bazaar - 28 April 2020 3:19pm

West of Chase County State Fishing Lake - 11 December 2019 12:59pm

North of Thurman Creek on the Dobbins Ranch - 24 November 2021 3:49pm

Bluff west of Thurman Creek on the Dobbins Ranch - 8 November 2021 6:13pm

A storm front approaching the Thurman Creek watershed south of Matfield Green - 15 June 2022 6:58pm

Open range west of Matfield Green - 31 October 2020 11:28am

The east pond, upstream from Thurman Creek, on the Dobbins Ranch mid spring after a prescribed burn - 28 April 2022 7:10pm

Upturned bedrock on the west bluff above Thurman Creek south of Matfield Green - 28 April 2022 5:25pm

A buck standing upright as a doe passes on the east bank of the South Fork Cottonwood River east of Matfield Green – 23 April 2023 6:17pm

Comet Neowise seen from open range west of Matfield Green - 24 July 2020 11:27pm

A cloud reflection in a tributary to Coyne Creek - 23 April 2020 3:21pm

Three bird nests in a copse of honey locust saplings near Coyne Creek -23 April 2020 2:51pm

Switchgrass blown into Den Creek - 8 December 2019 12:34pm

A leopard frog at the mouth of Chase County State Fishing Lake - 4 October 2021 2:49pm

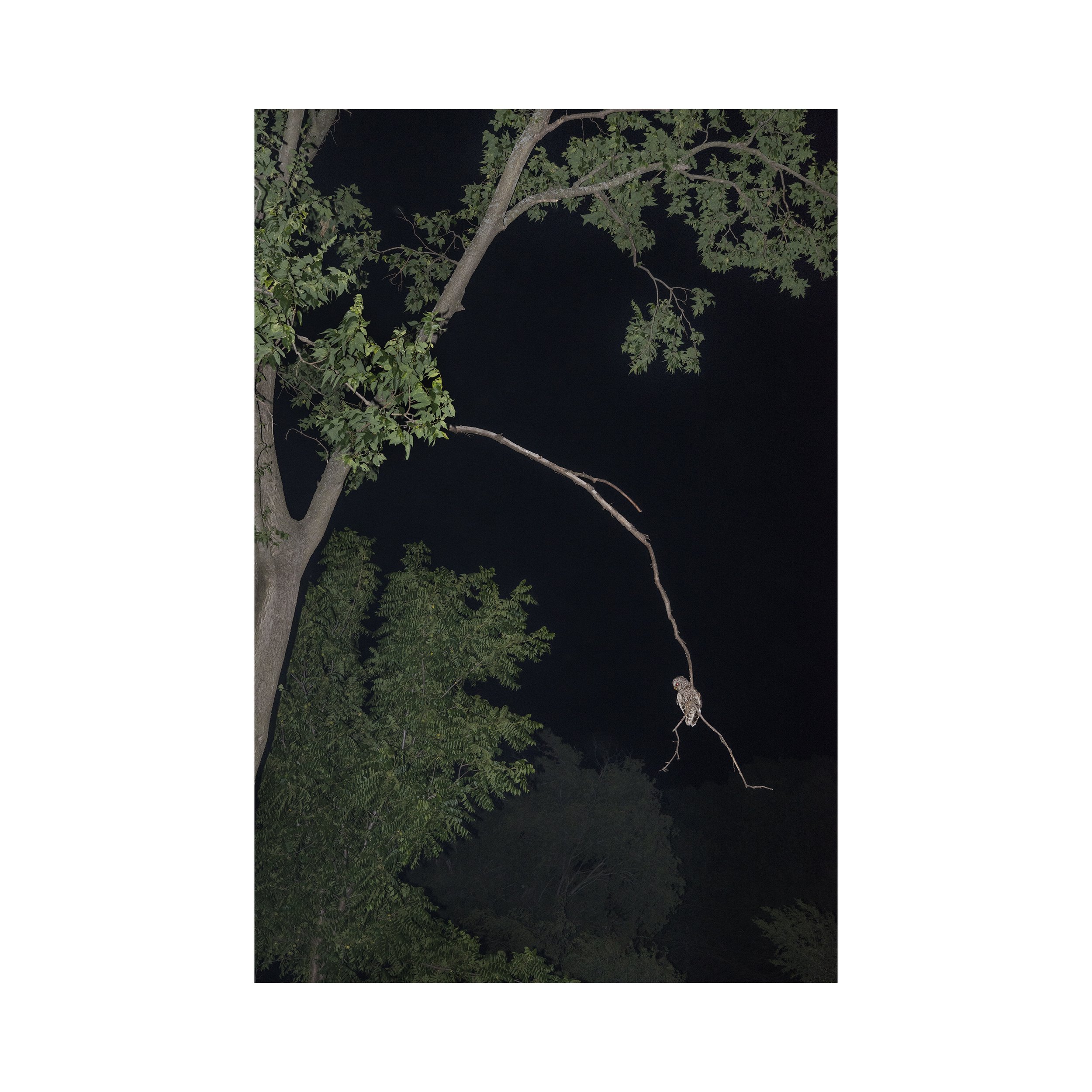

A barred owl in the back yard of 103 South Cameron Street, Matfield Green - 28 June 2020 10:02pm

Zack Bell's goat Molly reclining on the bank of the South Fork Cottonwood River - 3 July 2020 8:15am

Zack Bell's horse Bird in her pasture near the South Fork Cottonwood RIver - 3 July 2020 8:53am

Burl on a strangely bent cottonwood tree in the Tallgrass National Preserve - 29 May 2020 10:03am

Doug warms a juvenile rat snake in his hand in sunshine - 5 November 2020 11:16am

A blue heron that expired from electrocution after landing on a high tension power line north of Matfield Green - 27 June 2020 5:47pm

Burn with a twister along G Road south of Clements - 31 March 2021 2:36pm

A bird fleeing a prescribed burn along G Road south of Clements - 31 March 2021 3:30pm

Numerous hawks circling a prescribed burn, hunting for fleeing rodents, along Madison Road - 18 April 2022 5:03pm

Burn with dense smoke along G Road south of Clements - 31 March 2021 2:37pm

Billowing smoke from a burn near L Road south of Clements - 31 March 2021 4:10pm

After a prescribed burn on the Weiss Ranch east of Matfield Green - 28 March 2021 2:51pm

A deer running across a hilltop (with all four feet off the ground) after a recent burn south of Matfield Green - 14 April 2022 12:42pm

Looking south from Madison Road northeast of Teterville - 6 June 2021 5:07pm

A pond west of Matfield Station - 6 December 2021 6:06pm

A jackrabbit and a butterfly in spring grass uphill from Thurman Creek - 2 June 2022 4:45pm

Cardinal Flower in open range west of Matfield Green - 6 September 2020 5:21pm

Evie Mae's apple tree in the yard of the house at 103 South Cameron Street in Matfield Green - 8 August 2020 7:45pm

Along the South Fork Cottonwood River, east of Cottonwood Falls - 11 July 2020 7:33am

Sumac and Thistle on Pioneer Bluff - 25 September 2020 3:42pm

A possible dinosaur footprint on the Wight Ranch - 4 November 2020 8:56am

An archaic flint knife found on the Rowe farmstead near the confluence of Thurman Creek and the South Fork Cottonwood River - 29 May 2022 4:34pm

An armadillo feeding in a fallow field - 13 February 2022 3:11pm

A migrating snapping turtle near the northwest pond on the Dobbins ranch - 2 June 2022 - 6:15pm

The face of a migrating snapping turtle near the northwest pond on the Dobbins ranch - 2 June 2022 - 6:30pm

A writing spider at dawn east of Matfield Green - 11 October 2020 7:39am

A young opossum in the woods east of Matfield Green on the east bank of the South Fork Cottonwood River - 2 November 2020 9:19pm

The South Fork Cottonwood River at the Wight Ranch - 1 November 2020 8:41am

Greenbrier and honey locust - 5 & 10 December 2020 3:46pm & 4:49pm

A heron rookery on the South Fork Cottonwood River at Gladstone Station - 22 April 2021 3:08pm

Bald eagles guarding their nest on the Dobbins Ranch, south of Matfield Green - 24 April 2021 11:20am

A burr oak and redbud trees on the west bank of the South Fork Cottonwood River south of Matfield Green - 24 April 2021 10:34am

The small pond west of Thurman Creek on the Dobbins Ranch - 22 November 2021 5:53pm

Large-mouth bass from the small pond on the Dobbins Ranch - 8 November 2021 5:45pm

A wild turkey hen flushed from her nest in the watershed bottomland on the Dobbins Ranch - 3 May 2022 5:10pm

A wild turkey nest near the headwaters of the South Fork Cottonwood River - 30 April 2022 4:53pm

A frozen marsh west of Matfield Station on New Year's Day - 1 January 2022 1:40pm

Hoarfrost near the South Fork Cottonwood River - 17 December 2019 9:52am

Game trails on Sharpes Creek east of Bazaar - 16 February 2021 3:00pm

A honey locust branch in a blizzard north of Matfield Green - 17 February 2022 10:41am

Open range west of Matfield Station, -7 degrees Fahrenheit, with strong northerly winds - 10 February 2021 3:14pm

Near Thurman Creek - 12 January 2020 12:22pm

Two does on the west bank of Crocker Creek north of Matfield Green - 28 November 2020 5:28pm

A brook tributary to the South Fork Cottonwood River on the Bell Ranch, east of Cottonwood Falls - 1 February 2021 5:07pm

Spiderweb at the headwaters of the South Fork Cottonwood River - 7 October 2021 8:30am

Cottonwood north of Bazaar - 14 October 2020 12:51pm

A coyote trotting northward across Banks Creek south of Matfield Green – 8 February 2023 12:05am

Ten generations ago, at the end of the 18th century, grasslands covered 170 million acres of the North American Continent, from south of the Arctic Circle to the Gulf of Mexico, from the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi River basin.

Today, less than 4% of this ecosystem remains intact.

Most of the remaining prairie is found in the Flint Hills of central Kansas.

In November of 2019 I moved to the town of Matfield Green, with a population 46 at last count, in the middle of the Flint Hills, to more deeply explore an attraction for this region I’ve had since my youth.

I first saw this region when I was about ten years old. My older brother, who is a falconer, brought me with him to flush rabbits out of the grass for his red-tailed hawk to capture. I was just old enough to be awed by the landscape we were hunting in. I especially remember wondering what it must have been like for the nomadic people who inhabited the region before European settlement. The environment can be extremely harsh, even with the conveniences the industrial revolution has brought to our lives. When the weather is good, it’s easy to imagine how stirring the expanse of the prairie must have been to anyone moving through it on foot.

When I was older, I frequently came here to train and race bicycles. This gave me yet another kind of respect and affection for the environment.

Once I had committed to being a photographer, as a young adult, I began my first attempts to make photographs that sufficiently describe what is here, and discovered that, while it is easy to make pictures that are superficially pleasing, it’s extremely difficult to go beyond that.

My fascination for this challenge has endured for over fifty years now. Throughout the years I was living in Paris, San Francisco, northern Italy and Brooklyn, whenever I returned to the region to visit my family, I always set aside time to explore the Flint Hills.

I have also found myself consistently interested in the science, literature and art that relate to the prairie. Writings by Wes Jackson, Wendell Berry, Willa Cather, Mark Twain, William Least Heat Moon and Rachel Carson, among others, have informed and affirmed my experience. The photography of Robert Adams, Frank Gohlke and Terry Evans have given me ideas about how to more fully communicate the unique and subtle complexities of this environment. Joe Deal’s last body of work, West and West, has directly led me to explore the idea that it’s possible to make photographs that inspire imagining new ways to relate to the prairie environment in the future. His essay introducing that book of photographs elucidates conclusions my own work has led me to.

My father passed away almost three years ago. After his death, I found it profoundly fulfilling to spend time in the grassland. A few months after his death, an opportunity to move to Matfield Green arose, and I took it, with a great sense of excitement. For the first time in my life, I am living within the subject that I most want to photograph.

I have been living here for about two years at this writing. During the first year I learned my way around the area, became acquainted with many of my new neighbors, began experimenting with pictorial strategies, deepened my research into the science and literature of this region, and observed the passing seasons. This second year has led me to photograph more deeply, to revisit and revise my initial photographs with increasing clarity and purpose. I imagine this process could last a lifetime, but will yield a result appropriate to the scale of the subject after four to five years.

The grassland of the central North American continent has shaped, and been shaped by, the people who have lived within it since at least the end of the last ice age. If humans neglect or abuse the prairie, it soon becomes either inhospitable or changes into something else: maybe a cedar forest, or a dust bowl. Without the space of the Great Plains, our imaginations would be deprived of a potent metaphor for possibility, abundance and resilience. To spend time living in a grassland is to become subliminally connected to the central alchemical idea: As above, so below. The intermingling of forms, the echoes and symmetries of processes that determine and permeate these forms, are constantly apparent. Citizens of the prairie become intimate with otherwise unfathomable temporal and spatial scales, monopolizing both attention and action.

Silt in the flowing water of a creek and the dust cloud in the center of the Milky Way have similar visual appearances and mathematical characteristics. The scope of time and space here force certain conclusions that are as irrefutable and obvious as the force of gravity. Borders and property lines only serve to limit certain economic and cultural activities. Ownership is entirely a cultural construct. Its enforcement requires the constant threat of violence. As Teju Cole has pointed out that “There is no such thing as an innocent photograph of the American landscape.” Ownership implies, in part, a history of genocide and dispossession, death and life.

While mere footprints and remnants of fragile vegetation and aquatic life may remain for hundreds of millions of years, nothing is permanent. Catastrophe is an ever-present possibility, yet certain systems and structures have the resilience to endure extreme duress. Fire precedes and provokes renewal. Plants survive a constant onslaught of grazing animals and insects, extreme weather and fire by establishing roots and rhizomes deep underground. Fifteen feet below and fifteen feet above the horizon line, sunlight and rain meet soil and rock to produce sustenance for a profusion of life. Here, observation reveals the process underlying the substance.

I believe that this remnant of a once oceanic-scale ecosystem is rich with knowledge and metaphor that might, if persuasively and broadly communicated, allow new relationships, new systems of living, to be imaginable. While the pictures I make will serve as a kind of document of what exists here now, I especially hope they will be vehicles for envisioning possibilities for the future.

“It is not half so important to know as to feel … once the emotions have been aroused – a sense of the beautiful, the excitement of the new and unknown, a feeling of sympathy, pity, admiration or love – then we wish for knowledge about the object of our emotional response. Once found, it has lasting meaning.” -Rachel Carson